The human-to-robot service encounter (and robot-to-robot encounters)

On Tuesday, the 2nd of March 2021, Magnus Söderlund, Senior CERS Fellow, and Professor at Stockholm School of Economics held a seminar on recent empirical findings in human-to-robot and robot-to-robot interaction in the service sector. During this seminar, Söderlund talked about how such research can be conducted, some of the results from recent studies, and his view of the publishing opportunities.

As Master’s Marketing students, we were incredibly excited to attend this research seminar. This blog will provide a description of the seminar as well as our individual perspectives.

Interaction with robots in the service sector

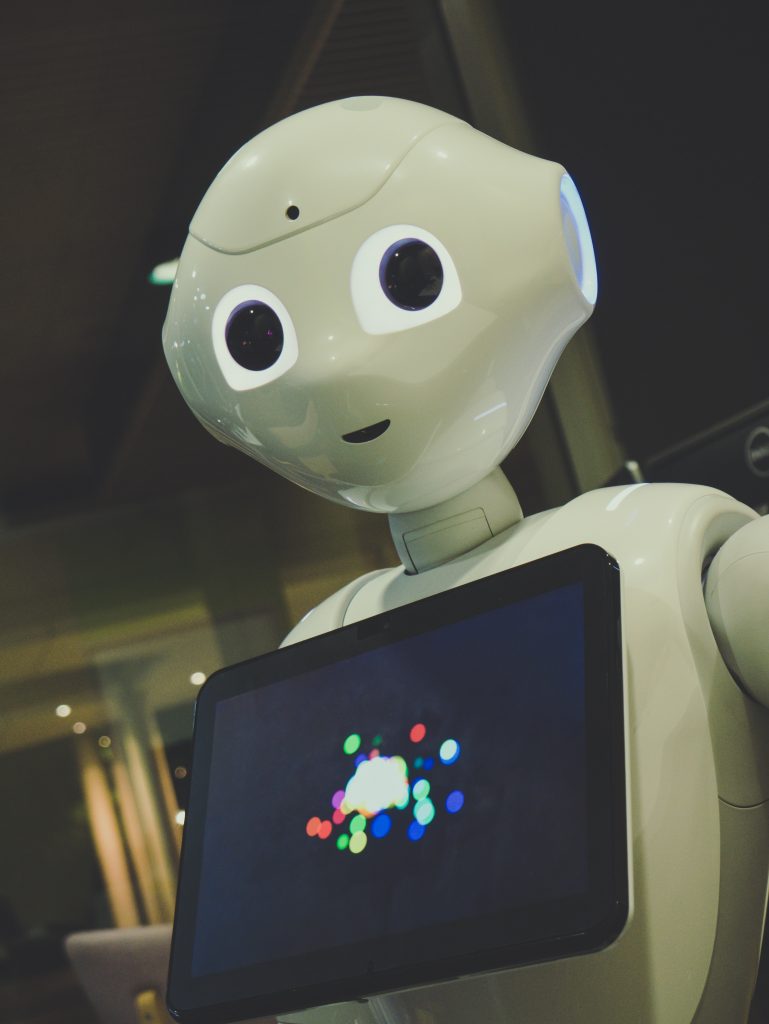

Robots are already making appearances in different service industries. For instance, a robot helping customers in supermarkets in Sweden and service robots in the Seoul Airport. However, according to Professor Söderlund, these instances appear to be more promotional stunts than integrated service experiences.

Professor Söderlund owns three robots with a range of functions. Currently under COVID-19 restrictions, Professor Söderlund has been getting creative with his experimental methods. Using his own robots and himself as actor, he’s been creating videos for the purpose of measuring viewer impressions on varying dimensions of robot interactions.

His video experiments are guided by theories of anthropomorphism and are designed to gauge viewer participants’ judgements of privacy violations, perceived service effort, and service politeness. Theories of anthropomorphism explore the imbuing of non-humans with human-like characteristics.

Distinct from Söderlund’s previous work on virtual agents, service robots will move within physical environments in which there are humans while collecting, storing, processing, interpreting—and possibly sharing—data about humans. To Söderlund, movement is necessary feature in service robots.

Professor Söderlund gave seminar attendees a preview of the preliminary results of his studies. Each examines different scenarios in which participants watch videos and give their immediate impressions. Here is a recap of the studies and their research implications:

Study 1 (Privacy Violation)

In this video, participants are introduced to a robot who records everything around it. One employee (played by Söderlund) is anxiously awaiting feedback from his manager on a project. The robot, who can access and share information it has recorded, is asked by the employee to reveal the feedback the robot overheard from the manager.

According to viewing participants’ reactions, the robot was evaluated as a human, based on whether he violated the manager’s privacy. Even when the robot revealed positive feedback—it was still considered to violate the manager’s privacy.

Implications: Anthropomorphism is clearly demonstrated here in ethical judgements on violations of privacy. The scenario indicates that robots in the workplace will be held accountable to the same moral standards as humans.

Study 2 (Privacy Violation)

In a twist on study 1, participants were shown scenarios comparing a human counsellor and a robot counsellor. After an employee had privately confided to the counsellor, a manager asks for the counsellor (human or robot) to reveal confidential information about the employee. As in study 1, the robot’s violation of the employee’s privacy is perceived the same as if a human did it.

Implications: Again, the robot’s behaviour is held to human schemes of moral judgement. In the case of violating privacy, participants notably placed human-based ethical concerns on the robot.

Study 3 (Perceived Effort)

According to previous research, employees seen doing effortful activities are perceived as providing better service. Söderlund was interested in whether this phenomenon also applied to robots. When viewing a robot struggling to complete a task, the robot was NOT viewed as providing “better service” when it struggled more, unlike humans.

Implications: While high-effort human activity is usually perceived as contributing to better service, the opposite is true for robots. This suggests that for humans to perceive service robots as performing high-quality service, the activity must appear easy. Perhaps this expectation of perfection from robots will limit the adoption of service robots until they are sufficiently capable to make it “look easy”.

Study 4 (Robot-to-Robot interactions)

Söderlund showed participants a video of a little robot instructed to go the kitchen and complete a task. However, when it gets there, it must first interact with the “kitchen robot” who has authority over the whole kitchen. Two scenarios played out: one in which the kitchen robot was polite to its subordinate, and one in which it was rude. Not only did participants agree that between the two videos the robots differed in their level of politeness, but also judged the rude robot as providing poor service.

Implications: Like Söderlund’s research on the perception of the happiness of virtual agents, future service robots will be interpreted based on their behaviour as though they were human. This will carry over into the judgement of their service politeness, even when serving another robot.

Conclusion

According to Professor Söderlund, service robots will be most likely start out as information storing devices or simple communication machines. However, their possibilities include processing and interpreting data as well. While many human jobs are not at risk, robotics and technology threaten jobs in the same way that farming equipment replaced animals. His current studies lead him to conclude, “we evaluate robots similarly to how we evaluate humans in similar situations”.

Concluding the seminar were some final thoughts from participants. Professor Mahr pondered potential “rage against the robot” in discussing frustrated behaviour towards service robots. Professor Ciuchita commented, “let’s make them smart, but not too smart” in reference to claims that Spotify’s shuffle feature appeared not random enough to many users. In conclusion, Professor Söderlund urged interested researchers to contribute to future service robot research. Currently, Söderlund is exploring the publishing landscape and looking for publishing opportunities in service or robotics journals.

Student perspectives

Karolina Jensen (Master’s Students at Hanken, Project Assistant at CERS):

“The opportunity to attend Magnus Söderlund’s seminar was a chance to experience the world of research in action. I found the research itself, and the results of the empirical studies conducted by Professor Söderlund thought provoking and inspiring. How far can we go with robot – human interaction in the service sector? And where will we be in 5- or 10-years’ time? I think being in the midst of an ongoing conversation on current research is incredibly motivating for a student, makes you want to learn more and maybe even find out for yourself.”

Erkki Paunonen (Master’s Students at Hanken, Project Assistant at CERS):

“This seminar provided a new perspective to research methodology during COVID-19 related distancing. Professor Söderlund introduced his methodological choices for these studies by jokingly referring to the ‘what would you do’ scenarios that researchers often describe to participants. If you can simply show them that scenario rather than describe it, why not? Using his own robots and self as actor, the methodology really struck me as a clever adaptation to remote research. Finally, as a student, it can often feel like academic articles are finished works that descend from the skies. It’s nice to hear about works in progress and realize that a lot of the research process is about doing, not just analysing.”

By Karolina Jensen and Erkki Paunonen

Master’s Student at Hanken, Project Assistants at CERS