What kits are

Bozer and McGinnis define kits as “a specific collection of components and/or subassemblies that together (i.e., in the same container) support one or more assembly operations for a given product or “shop order.”” (Bozer & McGinnis, 1992). In the process of kitting to feed assembly lines, it is important to prepare the kits at a pre- assembly line point. This step in effect acts as a consolidation point of non-value adding steps for material to be regrouped and assembled in a specific set of items with a specific purpose before being brought to the line or being stored. Kitting at different points of the supply chain influences how kits are transported and warehoused and may lead to economies of scale and costs reductions.

During the preparation of the kit, items are combined together based on the downstream needs after the point of kitting; kit preparation usually includes time allocated for picking and assembling each kit. Some of these activities for preparing the kits regroup non-value adding activities and concentrate them at one specific step; these include the manual handling as well as the picking of items for the kit. In the case where kits are prepared and used at another location, this would also require an additional step for transportation which does not add any value. The value of kits comes out in the subsequent step when the kit is being used.

Kits offer a range of benefits. Indeed, they allow for more efficient space usage and material handling than other assembly methods. They improve quality for the final user by allowing for quality control during the kitting preparation process, offer a reduction of the time spent fetching and picking parts when using the kit and increase flexibility through the mix of items presented at the next step in the supply chain.

It is important to note that kits also have some downsides; the main one is kit preparation which is labor intensive, requires space, time and extra management and planning. Apart from these problems related to the preparation of the kit, other issues might arise related to the quality of the materials linked to the kits. Indeed kit pieces that are defective can create part shortages on the assembly line and force the cannibalization of kits as well as stock outs. Defective materials might also lead to incomplete kits being stored as work in progress increasing inventory space required and lead times and risking the delivery of incomplete kits.

Kits in the humanitarian context

Indeed, even outside the context of factory production, kits still play an important role and help address issues faced by humanitarian supply chains. There are ten major humanitarian organizations that procure kits from suppliers to distribute them in the field (Berger, 2013) in case of a humanitarian crisis. The type of humanitarian crisis will often dictate what sort of kits are needed which can vary widely and be made up of medical kits, educational kits, water and sanitation kits, kitchen kits, winterization kits and any other type of kits according to the needs.

Kits are part of the response activities of the main humanitarian organizations (Berger, 2013). They can be relatively simple to be directly given to the beneficiaries or extensively complicated to cover a broad need such as the Inter-Agency Health Kit (World Health Organization, 2011). Organizations such as UNICEF manage an important number of kits every year.

In the context of disasters, kits are an important part of preparedness and response and are included in strategic procurement decisions and warehousing operations (Blecken, 2010). One of the characteristics of kits that interest humanitarian organizations is how they enable being reactive to events (Chandes & Paché, 2010). When disaster strikes time to react is short and having pre-picked and assembled kits for specific bundles of needs allows to reduce non-value adding activities and increase timeliness in the response phase. The preparation phase can also include all activities related to planning of material combination and quality control to ensure that the material is adequate for the response. In the response phase, kits offer quality, flexibility, rapidity and standardization especially in the initial phases of the response (Charles, et al., 2010; Kovàcs & Spens, 2007; Scholten, et al., 2010). The reconstruction phase however has more of an emphasis on long term activities for which needs have been thoroughly assessed which reduces the usefulness of kits. Indeed, kits at this point might have superfluous items and shipping individual items might better address the needs of the people affected.

The wide variety and complexity of items needed to respond to emergencies across the world requires a special emphasis on acquiring the right capabilities to manage different items including kits. Kits are based on a range of knowledge such as field experience, scientific and technical knowledge and also involve inter organizational cooperation and partnerships with multiple actors to determine which items will be put together. This knowledge and relationships located at different points of the supply chain are supplemented by a physical infrastructure and information technology systems. Kitting in the humanitarian context offers similar benefits than those found in the private sector and help achieve quality, flexibility and timeliness for emergencies.

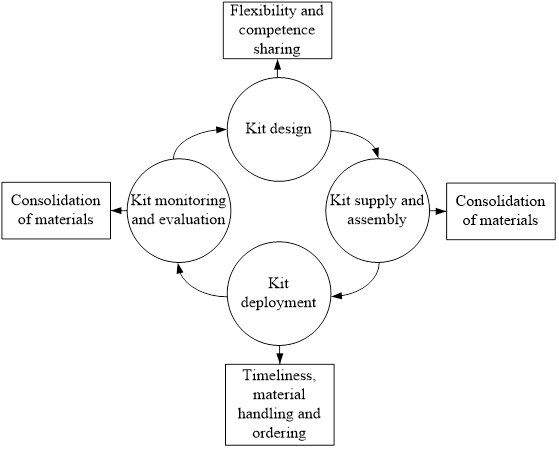

Kit management phases in the humanitarian context

Kit design which includes the task of deciding which items to regroup in a kit is based on technical knowledge of relevant guidelines, practical field knowledge, knowledge of market for supplies and partnerships with other organizations. Kit design helps improve outcomes in an emergency in two ways. First, it allows flexibility to adapt to an unknown demand since kits are designed to cover a certain range of needs. As these needs increase in complexity, the number of items and the mix of items are increased to help cover a range of possibilities. Second, kits allow to share competencies across the supply chain through the use of clear and specific standards based on relevant knowledge in their design. Downstream partner organizations which do not have developed such areas of knowledge will still be able to benefit from a kit designed with higher standards than which they could develop themselves.

Kit supply and assembly does not differ much from the standard business approach where items are consolidated together based on the downstream needs after the point of kitting. Kits can be supplied and assembled in large central warehouses with automated lines or in smaller field warehouses according to the needs and type of items in the kit.

Kit deployment offers the obvious benefit of a fast response if the proper kits are supplied and assembled before a crisis. With the packaging of items together, kits can also play a role in facilitating supply chain activities related to material handling, transport and storage. Furthermore, when kits are deployed in a disaster setting, the knowledge of standards and of the related item quantities will facilitate the order process by responders.

Finally, the kit monitoring and evaluation process helps build on local knowledge and develop technical expertise to improve kitting activities and plays an important role to develop appropriate kits. This step serves as a way to obtain feedback, improve and diffuse internal and external organizational knowledge and is required as kits in humanitarian activities are not designed for a client with precise specifications for a production line.

Kit management phases and the benefits they achieve

To contact the autor: ac6538@coventry.ac.uk

References:

Berger, K., 2013. Procurement policies in disaster relief, Jönköping: Jönköping International Business School.

Blecken, A., 2010. Supply chain process modelling for humanitarian organizations. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 40(8/9), pp. 675-692.

Bozer, Y. A. & McGinnis, L. F., 1992. Kitting versus line stocking: A conceptual framework and a descriptive model. International Journal cf Production Economics , Volume 28, pp. 1-19.

Chandes, J. & Paché, G., 2010. Investigating humanitarian logistics issues: from operations management to strategic management. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 21(3), pp. 320-340.

Charles, A., Lauras, M. & Van Wassenhove, L., 2010. A model to define and assess the agility of supply chains: building on humanitarian experience. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 40(8/9), pp. 722-741.

Kovàcs, G. & Spens, K. M., 2007. Humanitarian logistics in disaster relief operations. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 37(2), pp. 99-114.

Scholten, K., Scott, P. S. & Fynes, B., 2010. (Le)agility in humanitarian aid (NGO) supply chains. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 40(8/9), pp. 623-635.

World Health Organization, 2011. The interagency emergency health kit 2011: medicines and medical devices for 10 000 people, New York: Publications of the World Health Organization.