30.04.2021

Andries Heyns is a postdoctoral project researcher at the Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Research Institute. In this blog post he shares his ten-week experience as a Geographic Information System specialist for Doctors Without Borders in the Tigray refugee camps in Sudan

All images by Andries Heyns

Early in November 2020, conflict broke out in Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region and refugees started fleeing in their masses to neighbouring Sudan. The journey requires crossing up to 350 km of mountainous terrain over days and weeks, in dry conditions with temperatures regularly exceeding 35 degrees Celsius. Lacking basic resources like food and water, carrying only what they can, carrying their children and those too weak to walk, they arrive in Sudan dehydrated and exhausted. As if this isn’t challenging enough, they also carry the trauma of seeing their families killed, their livelihoods destroyed, and having their futures cut short. With no short-term solution to the situation in sight, these refugees are settling in challenging, resource-scarce environments, with no idea of what the future holds for them.

At the end of November 2020 I was asked by Doctors Without Borders to provide field support as a Geographic Information System (GIS) specialist in the refugee camps in Sudan. This followed my previous field work for MSF, as a logistics manager in the conflict-torn Central African Republic in 2016, once more as a logistics manager for a cholera response in Mozambique in April 2017, and then as a GIS specialist in Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh at the end of 2017 (a video summary of GIS field work can be found here). I arrived in Sudan early in December 2020 and stayed for a total of ten weeks, returning mid-February 2021. I was based in Gedaref, from where I visited refugee camps in Hamdayet, Al-Hashaba, Umm Rakouba and Al-Tanideba (see Figure 1). Hamdayet and Al Hashaba are, in theory, – transit camps – refugees arrive here first, register and stay temporarily after which they are relocated to the permanent camps, namely Umm Rakouba and Al-Tanideba. However, in reality, people were forced to stay much longer.

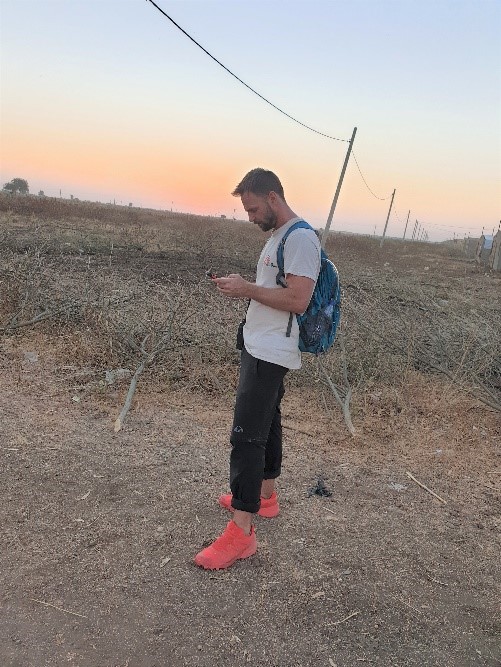

As a GIS specialist my main responsibility was to collect spatial data of importance to refugee camp monitoring and management. When we know where the populations are within the boundaries of their settlements (i.e. how they are dispersed), and when we know where their immediate needs are most urgent, we can plan our intervention more effectively to address shortcomings. From an operational perspective we also need to keep planners and decision makers who are not actively on the ground informed about the evolution of the situation. One manner of providing them with a concise summary of this big picture is with detailed and up-to-date maps. A map can tell a visual story and provide context and scale within a single picture frame, and comparing maps over different time frames provides insight into the progress of humanitarian aid activities and the growth of the camps. However, with refugees arriving on a daily basis, the picture is constantly changing and needs regular updating so that a current picture is available at all times. This required me to spend a lot of time crossing refugee camps on foot, with a bag full of water on my back, two smartphones for data collection (one spare just in case), sunscreen, and some snacks.

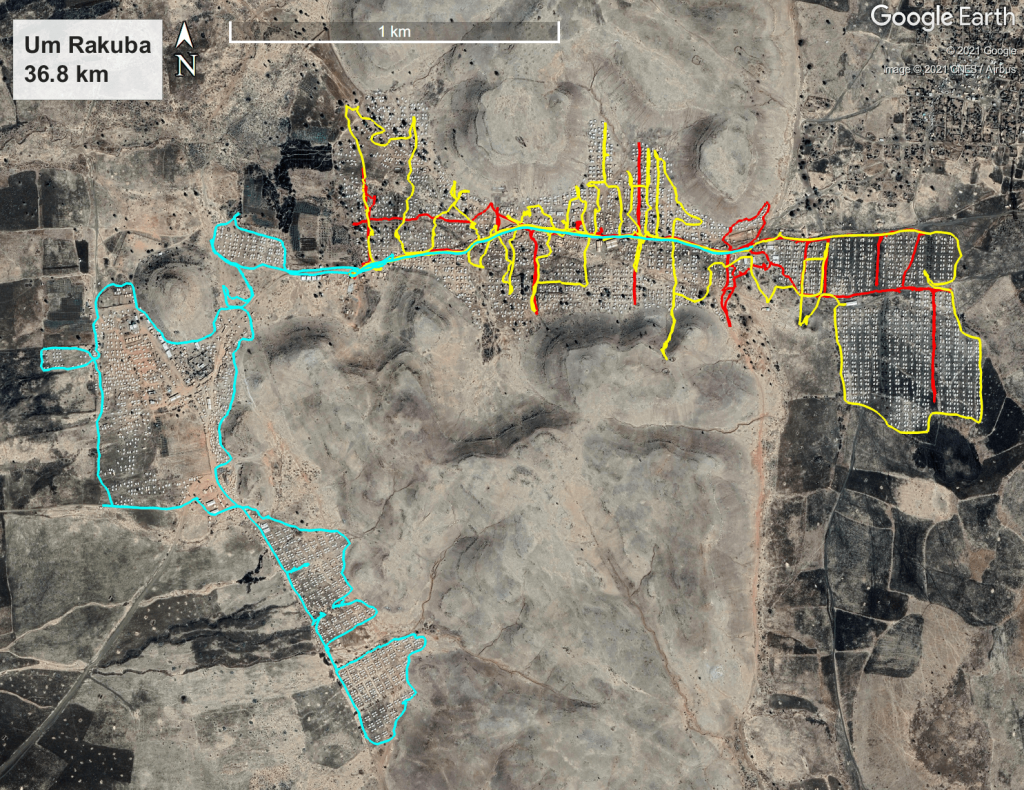

During my visits I collected GPS coordinates of points of interest, sometimes drawing mini-maps and taking photos for verification later, and I then transferred and processed this data at the end of the day to put on maps. The points I took were primarily the location and condition of water and sanitation facilities, the locations of other actors (UNHCR, WFP, Red Cross, etc.), and the rapidly changing extents of the camp boundaries. In camps like Um Rakuba and Tenedba I had to go back more regularly, since these camps were receiving refugees from Hamdayet and Al Hashaba and were evolving at an astonishing pace – thus requiring constant additions and updates to the datapoints. This burden was often eased with the aid of MSF’s GIS support community, e.g. when they obtained satellite data and dwelling density analyses for me, helping team members on the ground to estimate the refugee population size and their distribution. This, in turn, helps to determine gathering points for activities such as vaccinations. I also regularly received GPS coordinates from other team members from the various camps, which I then turned into maps and sent back to them.

Performing this work was physically exhausting. I generally traversed at least 8 km on foot each time I went to the camps, with temperatures normally above 35 degrees, and no shade. In total I covered 94.5 km on foot in all my visits.

Maps and data of all my activities were presented in various formats, depending on user requirements. Most maps were standard pdf documents, while some datasets were exported to Google Earth for more interactive viewing purposes, and other datasets were loaded to the team members’ smartphones for navigation purposes around the camps.

Back at the base in Gedaref, power cuts came and went unexpectedly, generally lasting two or three hours, but sometimes lasting well over four hours. Internet access was very weak to non-existent most of the time, which was very challenging to deal with because I need internet to do my job. However, having been in the field before, this wasn’t unexpected and it did not bother me too much – I was always able to get the job done, just with some delays here and there. To get to the camps required long journeys, but with unique scenery like hundreds of camels being herded by small boys or crossing a river by ferry to get to Al-Hashaba. When you arrive at the ferry, there is no certainty if you will get on the next one or if you will have to wait longer, but nobody seems to care too much. That’s just the way it is, the pace of life is different and you just go with whatever happens.

My time back in the field made me realise that I want to do more hands-on humanitarian work and be more directly involved in response planning and coordination. I will therefore be joining MSF’s UK office in London at the end of May to work as a GIS coordinator, providing support to the Manson Unit – which focuses specifically on health policy and practice. I will nevertheless remain affiliated with Hanken, and will continue working with HUMLOG on smaller projects.