16.04.2021

Matthew Kern is a Masters student in the Humanitarian Logistics track and in this blog entry he shares his experience as a Logistics and Procurement Intern with LWF

News that Europe was suffering from a second wave of the COVID pandemic came in mid-November, yet it could not have been less relevant to the lives of those in the rural town of Meiganga, Cameroon, near the border with the Central African Republic (CAR). Between daily electricity cuts, occasionally for multiple days at a time; over 40% of the population getting malaria every year; and children routinely going to the hospital for food or waterborne illnesses, there were plenty of more imminent health concerns. Despite this, the area was blessed by relative stability in comparison to the region. Boko Haram attacks, that made international news, were 400-500 km to the west and armed rebel groups, kidnapping and stirring violence in CAR’s civil war, were 300-400 km to the east. Both conflicts are completely separate from Cameroon’s own slow-moving civil war in between the English and the French-speaking regions, in the southwest part of the country.

Meiganga’s stability was fostered by the presence of a Rapid Intervention Battalion (Bataillon d’Intervention Rapide) based 3 km outside of town. The international NGOs took advantage of the situation for their regional bases. If a Toyota Landcruiser was seen on the road, it could have been the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), World Food Programme (WFP), International Red Cross, Solidarity International, Plan International, Norwegian Refugee Council, Danish Refugee Council, the UN Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) or the Lutheran World Federation (LWF), who I had the pleasure to work for.

I had the opportunity to get connected with LWF through Hanken’s Humanitarian Logistics Department and attended a four-month field internship at the Meiganga headquarters in the fall of 2020. LWF is a global group of churches that has a World Service branch “dedicated to challenging and addressing the causes and effects of human suffering and poverty, linking local responses to national and international advocacy” (LWF, 2021). Their global operations focus on long-term development in three categories: Livelihood, Quality Services, and Protection/Social cohesion. The various offices implement these programs on an as-needed and as-funded basis.

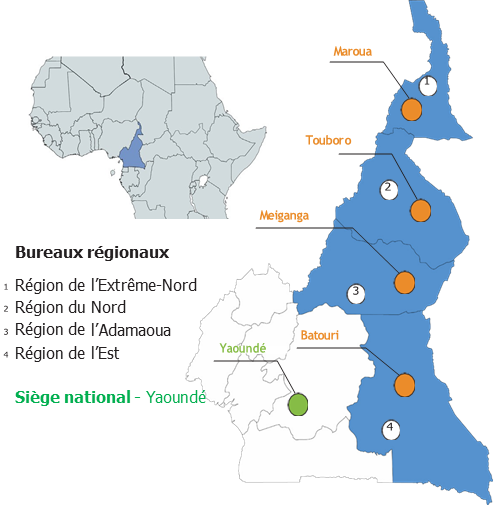

LWF has been active in Cameroon since 2015 when large numbers of refugees began crossing borders in the Extreme North, North, Adamawa, and East region. Currently, LWF is a partner of different State and UN actors for various projects throughout the country including the UNHCR, US government (PRM), Government of Germany (BMZ), WFP, and UNICEF. The Meiganga headquarters focuses on peace and livelihood activities. Livelihood programs are mainly centered around agriculture, providing tools, seeds, and animals for production, while the peace programs run in tandem to open dialogue between local villagers and refugees who have settled in the community.

As a Logistics and Procurement Intern, my role in aiding this situation was relatively minor. However, I was fortunate to work on numerous projects benefiting refugees and I experienced the challenges of working in the field firsthand. The highlight of the internship was working on an end-of-the-year procurement project funded by the UNHCR.

In mid-November, the UNHCR discovered unused budget funds for 2020. This led to the commission of LWF with the procurement and distribution of hardwood student desks, packets of underwear for young girls, and bars of laundry soap to 8 school districts in a 5-week time. Three years prior, LWF had completed a similar project that took 3 months. The request of the UNHCR to take the project was not seen as optional as the organization’s budget solely depended on their partner status with the UN. The term “pas facile” or “not easy” was said with extended breath often in those days.

The procurement process involved publishing bid requests in the newspapers of two major cities, Yaoundé and Douala, and a day trip to search for suppliers in the regional capital, Ngaoundéré. Once the extensive technical bids, some hundreds of pages long, were received the procurement committee gathered for over 20 hours over 2 days to complete a Competitive Bid Analysis (CBA). The request for bids stated a timeframe of 3 weeks for production and delivery, the CBA was completed the last week of November with the UNHCR expecting the 1,500 hardwood desks, 3,742 pairs of 6-pack underwear, and 4,000 bars of laundry soap, to be procured and delivered by January 1st. Other than being short on time, the challenges to this process were:

- Few of the current staff were present for the previous student desk project years before however, so there was little experience in this type and volume of procurement.

- The sheer number and specifications required of

hardwood desks in which:

- No single supplier had the capacity to make more than 300 hardwood desks;

- Each desk had to be made with a specific type of wood to ensure a long life, however, that wood was not grown in the region.

- The closest school was over an hour off the paved road by truck, with most schools 2-3 hours away, taking a freight truck 4-6 hours to travel the same distance.

- All desks were to be assembled on sight, meaning if there were errors in the production, they would be impossible to fix without another delivery.

The purchase requests were broken into manageable lots and a dozen suppliers were chosen based on having proper documentation, price, quality, capacity, and location. My role was administrative, mainly ensuring that the voluminous amounts of paper were organized and optimized so those on the committee could focus on the decision-making process. The procurement process in LWF is still paper-based, with physical signatures required on dozen documents from every decision-maker in each purchase. Due to the size, the procurement had to be authorized by the Country Representative. That meant that thousands of pages had to be signed or initialed, scanned, digitally organized with previous documents, and sent to the Country Representative before approval. During this process normal work matters were ongoing, meaning that I had to work through the night to prepare the documents for signature and sending before numerous staff members left at 6 AM the next morning for field visits with the UNHCR. All the documents were completed and before I departed from Meiganga, we received and counted the 3, 742 underwear packets and made a site inspection of the first desk delivery to 3 school districts.

As we went through the classrooms teeming with children, it was a moment after months of Excel spreadsheets and managing paper that I could see my actions had, in the smallest way, facilitated thousands of students having a better learning environment.

However, for the organization, the mad dash did not help them in the end. Supplier deliveries ran in mid-January and, with the backdrop of COVID, the UNHCR Cameroon reassessed the budget of LWF, reducing it by 45%. This caused many layoffs with the expectation that LWF would service the same number of beneficiaries as the year prior, demonstrating the fickleness of working within the UN umbrella.

References:

LWF (2021) LWF World Service is the humanitarian and development arm of the LWF. [online] Available at: <https://www.lutheranworld.org/content/about-dws> Accessed: 2 April 2021.