On May 20, a Finnish aid worker was kidnapped in Kabul, Afghanistan. The dreadful incident included the murders of a German aid worker and an Afghan security guard. (1) Once again, we are reminded how dangerous humanitarian work can be.

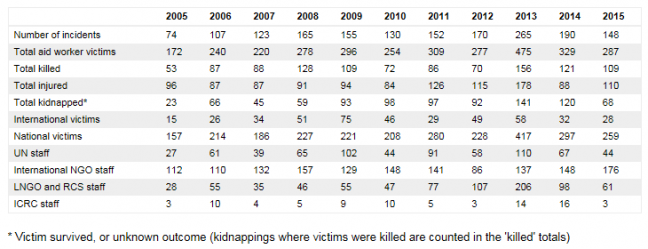

ALNAP estimates that there were 450,000 humanitarian aid workers globally in 2015. (2) As shown below, 287 of them were killed, injured or kidnapped in 148 separate incidents. The proportions vary, but the preponderance of victims are always national (not international) aid workers.

Source: The Aid Worker Security Database (https://aidworkersecurity.org/incidents/report/summary)

This year, through May 20, an estimated 106 humanitarian aid workers have been attacked. A very large majority of these victims (98 out of 106) are nationals of the countries in which the attacks occurred. The most dangerous countries for aid workers in 2017 are Syria, South Sudan, Somalia and Afghanistan. Of the 106, 56 were killed, 23 wounded and 27 kidnapped (https://aidworkersecurity.org/incidents/search?start=2017&end=2017&detail=0).

Miklian et al. found, as expected, that countries at war are more dangerous for aid workers. However, surprisingly, whether combatants follow the “rules of war” appears to have little impact on the danger – they found no evidence that conflicts where combatants actively target civilians present higher risk for aid workers. Interestingly, countries in which NATO forces are deployed may experience fewer attacks on aid workers, while nations with UN peacekeeping missions have more attacks.(3)

Facing such danger, what’s a humanitarian to do? There are three primary strategies: stay away and avoid the danger; ignore the danger, until it appears without warning; or mitigate it, using techniques of proactive risk management.

To Avoid, Ignore or Mitigate?

Avoiding means staying away (for the internationals) or getting out (for the nationals) by joining the ranks of refugees leaving their home countries. This can be very disruptive for the national departing as a refugee. It also leaves the victims of disasters, in urgent need of help, to handle it themselves.

Ignoring implies living (and sometimes dying) in the shrinking humanitarian space (i.e. the ability to deliver aid, unhindered in a secure environment).(4) Overall, the risk seems small – only 287 out of 450,000 humanitarian aid workers were reportedly attacked in 2015. Of course, in certain countries the likelihood of trouble is much greater.

Some opportunities to make a difference are so dangerous that avoiding them may be the only sensible course of action. Other opportunities may be so safe that ignoring any hint of danger is reasonable. Still others, arguably the majority of humanitarian assignments, can benefit from a mitigation strategy.

Mitigating involves assessing vulnerabilities, in terms of likelihood and severity of impact, across the humanitarian supply chain. Supply chain mapping and collaboration among NGOs can help identify vulnerabilities and develop proactive plans. In many countries, identification with NGO logos or symbols (e.g. the Red Cross or Red Crescent) makes aid workers safer. In some countries, such identification paints targets on their backs. The deployment of armed and trained security professionals, whether civilian or military, is another tactic for keeping danger away from aid workers. But visible security teams can also attract the attention of those determined to disrupt humanitarian relief work.

Being aware – and having a good exit strategy – may be the best response to the perils faced by aid workers today. Perhaps the ultimate goal of humanitarian work is to bring everybody home, from beneficiaries to international aid workers, alive and well.

1. Teivainen, Aleksi (2017), “Finnish aid worker kidnapped in Kabul, Afghanistan,” Helsinki Times, May 22.

2. The State of the Humanitarian System, 2015 Edition, ALNAP (http://www.alnap.org/resource/21036.aspx).

3. Miklian, Jason, Kristian Hoelscher and Håvard Mokleiv Nygård (2016), “What makes a country dangerous for aid workers?” The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2016/jan/18/what-makes-a-country-dangerous-for-aid-workers.

4. EU (2010), The Humanitarian Space Increasingly under Threat, European Commission, http://ec.europa.eu/echo/files/media/publications/humanitarian_space_en.pdf.