By Helleke Heikkinen

Doctoral Researcher at the department of Supply Chain Management and Social Responsibility

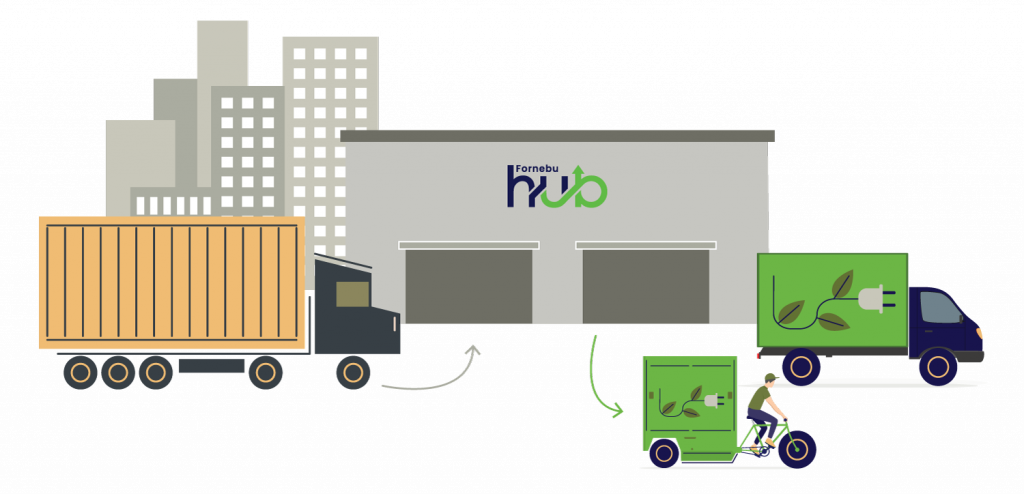

Image source: https://www.fornebuhub.no/

(Fornebu hub UCC has been a part of the research project)

Due to urbanization and, especially since the pandemic, rising numbers of e-commerce deliveries, cities are increasingly paying attention to city logistics solutions that would both decrease traffic and emissions. One such solution is called an urban consolidation center (UCC). A UCC is usually a strategically located facility where goods are brought, sorted, and consolidated before being delivered to different city destinations. It could be located at the edge of the city center or close to places of demand, such as construction sites, shopping malls, or densely populated areas. If we use an e-commerce order as an example, the main idea is that instead of each order being dispatched separately from multiple stores or warehouses, it is collected, sorted, and packed at the UCC. From the UCC, deliveries are loaded onto smaller fleet vehicles, such as vans or cargo bikes, so they can be delivered within the city. Research has shown that this setup makes it possible to reduce the number of delivery trips that have to be made and reduces the emissions associated with each order, especially if the delivery is made during peak hours when city traffic is congested.

UCCs have many pros and good intentions. They can offer consumers and municipal facilities such as schools and hospitals faster and more predictable deliveries while helping reduce city traffic. UCCs allows for optimized delivery routes by combining deliveries and shipments from multiple businesses. It can also make using less-emitting vehicles like cargo bikes and electric vans possible. Fewer delivery vehicles mean less curbside parking pressure and improved pedestrian and cyclist access. This can help cities make urban space more accessible and attractive.

However, setting up a UCC is not as straightforward as it might sound. Many stakeholders are involved, such as city authorities, retailers, logistics service providers (LSPs), and urban residents. All Stakeholders’ needs must be balanced when choosing the location and operational model of the UCC. Costs and potential benefits need to be considered. Setting up a UCC requires substantial infrastructure investments, including warehouses, sorting technology, and choosing suitable delivery vehicles. When choosing these vehicles, one must consider how well they fit with the city’s infrastructure and seasons. For example, cargo bikes can be challenging to operate in Nordic cities in wintertime. This means the upfront costs can be a significant barrier for cities, logistics companies, or retailers to consider implementing a UCC.

Research has shown that, for example, retailers may not be very positive about using UCCs as their logistics services are typically already provided by their LSP partner. However, if restrictions or sanctions are put in place, or other costs increase, they might become inclined to use UCCs. There is also a risk that smaller retailers might face higher costs per shipment as the fees for consolidation can outweigh savings from reduced operations.

The success of a UCC depends on cooperation between municipalities, logistics providers, and retailers, which is often challenging. Stakeholders may have conflicting priorities, with some resistant to centralized consolidation due to concerns about losing control over their supply chain, competitive advantages, or problems with integrating different software solutions. This is why the operating model chosen for the UCC is crucial. There are models when local city governments partly fund or subsidize the UCC, but there are also private sector-owned and operated UCCS, typically run by a logistics company. There is also a combination of public-private partnerships where the UCC is co-funded by both the public sector and private-sector companies and cooperative models where retailers pool their resources to operate a UCC. Another option is a third-party-operated model where a third party establishes a UCC and operates it, providing services for retailers, LSPs, or municipalities. All these different models come with distinct pros and cons that need to be balanced when choosing the setup.

These challenges raise the question of whether UCCs are a smart solution for improved and sustainable city logistics. The improvements UCCs can bring highlight cities’ need to reduce emissions and traffic on city streets. This way, many of the upsides of UCCs are associated with the goals cities have for improved and sustainable city logistics. However, many of the downsides are challenges for stakeholders such as retailers and LSPs who carry uncertainty. This way, city authorities play a crucial role in adopting UCCs as they can function as an instigator, choosing the operating model, findings a location, and balancing stakeholder needs while using their authority and policies to further UCC adoption. Here, the city needs to make sure not to interfere with fair competition so as not to favor any operator or stakeholder. Still, subsidies and city investments are likely inevitable if a shared UCC model is to be implemented. It also needs to be noted that if e-commerce orders keep increasing, no amount of efficiency can remove added packaging needs or emissions from increased deliveries, as the root cause is consumption and online ordering. No amount of efficiency can reduce externalities if consumption keeps increasing. However, good solutions are also needed for other deliveries, such as city internal deliveries for hospitals, schools, and businesses.

To conclude, it is fair to say that UCCs offer a promising solution to improve logistics efficiency and reduce the environmental impact of city deliveries. However, careful planning and robust stakeholder alignment are crucial to overcoming the challenges. When implemented well, UCCs can support urban sustainability goals, but a scalable and cost-effective model that truly considers stakeholder needs remains a work in progress and will look different for different cities.

Presentation of the LOGIN project: This blog post is part of the Nordic research collaboration project LOGIN. The project aims to investigate what municipalities can do to encourage businesses to develop and scale up sustainable business models for urban distribution and provide municipalities with governance methods to enable and steer the development and testing of city logistics and last mile logistics solutions. More information can be found here!

References and further reading on UUCs:

Akgün, E. Z., Monios, J., Cowie, J., & Fonzone, A. (2024). The retailer perspective on the potential for using urban consolidation centres (UCCs). Research in Transportation Economics, 103, 101413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2024.101413

Akgün, E. Z., Monios, J., Rye, T., & Fonzone, A. (2019). Influences on urban freight transport policy choice by local authorities. Transport Policy, 75, 88–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2019.01.009

Björklund, M., Abrahamsson, M., & Johansson, H. (2017). Critical factors for viable business models for urban consolidation centres. Research in Transportation Economics, 64, 36–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2017.09.009

Johansson, H., & Björklund, M. (2017). Urban consolidation centres: retail stores’ demands for UCC services. International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management, 47(7), 646–662. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-02-2017-0114

Helleke Heikkinen does research in supply chain management and sustainability, currently focusing on sustainable last mile deliveries and urban logistics. She has returned to research after ten years of working in various roles within startups, technology, and investment organizations. She wants to combine her interest in cities, sustainability, and innovation, while simultaneously adopting sensemaking and paradoxical theory perspectives in her research.

Helleke Heikkinen does research in supply chain management and sustainability, currently focusing on sustainable last mile deliveries and urban logistics. She has returned to research after ten years of working in various roles within startups, technology, and investment organizations. She wants to combine her interest in cities, sustainability, and innovation, while simultaneously adopting sensemaking and paradoxical theory perspectives in her research.